Durante’s Danza Fanciulla – imagining the dance

February 24, 2010

Danza, danza fanciulla is a song by Italian Baroque composer Francesco Durante (1684-1755). Loved and performed by singers across the world, this “Aria Antiche” will make part of a delightful programme Viva Italia, featuring Cape Town’s well-known singing partnership, soprano Beverley Chiat and mezzo-soprano Violina Anguelov, accompanied on the piano by Albert Combrink. The all-Italian programme includes familiar gems from the operatic repertoire – including Madama Butterfly, La Boheme and La Traviata – as well as Neapolitan songs.

Danza, danza fanciulla is a delightful invitation to the dance. The sound of the waves and the playful breeze are the accompaniment to this intoxicating frolic. Beautiful sounds such as the singing of the poet, mix with the glorious sounds of nature, inviting a young girl to let her spirit run free – and by implication also her body.

Danza, danza, fanciulla gentile (Text by an anonymous poet, in Italian)

Danza, danza, fanciulla, al mio cantar;

danza, danza fanciulla gentile, al mio cantar.

Gira leggera, sottile al suono, al suono dell’onde del mar.

Senti il vago rumore dell’aura scherzosa

che parla al core con languido suon,

e che invita a danzar senza posa, senza posa,

che invita a danzar.

Danza, danza, fanciulla

Dance, dance, gentle young girl

(Text by an anonymous poet, in free translation by Albert Combrink)

Dance, dance, young girl to my singing (song)

Dance, dance, gentle young girl to my (singing) song;

Twirling lightly and softly to the sound, to the sound of the waves of the sea.

Sense the vague rustling of the playful breeze

that speaks to the heart with its languid sound,

that invites you to dance without stopping, without stopping

that invites you to dance.

Dance, dance, gentle young girl to my song.

Durante: The composer whose sacred music overshadows the rest of his output.

Durante was born in Regno delle Due Sicilie (the Kingdom of Two Sicilies) at a time when it was the richest and most important of the Italian states before the unification of Italy. From a large family, his first musical influence was his father, a dedicated singer in the parish church. He entered the Conservatorio dei poveri di Gesu Cristo (The Concservatory of the poor of Jesus Christ) in Naples and later became a pupil of Alessandro Scarlatti. He later became a famous teacher of pupils such as Giovanni Paisiello, Giovanni Battista Pergolesi and Niccolo Piccinni, to name only a few. By all accounts, Durante was dedicated to his students’ welfare and education. Durante was, in turn, always spoken very highly of by his pupils. Unusually among Neapolitan composers, Durante had little interest in writing operas, although he did compose sacred dramas and secular as well as sacred cantatas. He made a name for himself chiefly in the devotional and liturgical genres of his day. Despite the dominance in his list of compositions of religious works, he also wrote a large number of successful harpsichord sonatas and toccatas, and eight Concerti per quartetto.

The uncertain history of Danza, danza fanciulla

Two popular arias attributed to Durante are published in anthologies of Italian songs – “Arie Antiche” collected by 19th century editors. Vergin, tutto amor and Danza, danza fanciulla are perhaps the only works for which Durante is still recognized. This is ironic since in his catalogue they would not hold a very esteemed place incomparison to the larger works and educational volumes he produced. In all probability they were only “solfeggios” or “singing exercises” to which elaborate accompaniment and text were added in the nineteenth century. He wrote many didactic works and even in non-didactic compositions there are signs in the actual printed scores that reveal the master-teacher at work. For example, in some of the masses elements of the plainchant or canon were marked as such for the edification of the student/performer. (Rachael Unite, All Music Guide )

Performance practice in Durante’s “Arie Antiche”

Given that the originals are now lost, performers have to rely on performing versions created and commissioned by 19th century publishers. Some of the editorial suggestions are appropriate, and without these wonderful “recreations” these melodies might have been lost for ever. However, one can not ignore the fact that when you hear these works performed, you are listening to a twenty-first century “imagining” of what the a 19th century editor (and therefore “minor” composer/arranger”) imagined what an 18th century composition might have sounded like. There is no saying that even the choice of text would carry the blessing of Signore Durante. There is no guarantee that the tempo indication given in the 19th century would be appropriate to a sound-world already a century old. In fact, apart form the melody, most of what we find in the published editions of this song, were added by other hands.

The metronome marking and the tempo indication of “Allegro con Spirito” are not Durante’s at all. The metronome had not even been invented yet, for a start. Singers have to interpret the song with the text as a starting point. Let’s forget for a moment that the text was not chosen – or set – by the composer, and accept its validity as a document. Given the lightness of the text – the references to delicate and playful breezes and rustling sounds of nature – the metronome marking given by the editors seems too fast and virtuosic. At 138 to a beat a whirling dervish is conjured rather than a simple “twirling lightly and softly to the sound”. Yet singers revel in the virtuosic display that the fast tempo affords. Thrilling as this might be, it makes the piece little more than a coat-hanger on which to hang an elaborate costume.

The piano used for accompaniment had not been invented yet when Durante wrote the melody. Even the dynamic indications are not “authentic” as it was a convention of the Baroque not to mark changes of volume – partly because instruments such as the spinet could only play at one dynamic level. Others, such as a harpsichord or organ, could not gradually change volume, but could only jump from one level to the next (“terrace dynamics”), given some technological device such as adding a few more strings or pipes.

What are performers in 2010 to do?

– Play it on the harpsichord or spinet?

This would recreate the keyboard sounds that Durante had available in his time. (But we do not have a harpsichord in our concert.) We are not even sure that it was actually written for a harpsichord. A spinet is unpractical in modern concerts as it is simply not loud enough to be heard properly more than a few feet away, let alone in a concert hall.

– Play it on a piano and imitate the harpsichord?

This is acceptable practice for keyboard works such as those by Bach and Scarlatti. Crisp articulation and not using the sustaining pedal, are used as techniques that outline the architecture of these works.

Here is a YouTube Clip of the piano accompaniment as it is published, recorded without a singer. This “Music Minus One” version illustrates the issues with the piano accompaniment as it stands. Pedals, legato double octaves and long sustained chords are used in abundance. None of these are technical devices employed in the Baroque – especially not on keyboard instruments.

Click here to listen to Danza, danza fanciulla (Piano Accompaniment Only)

In the case of Durante’s song and its “Arie Antiche” colleagues, the accompaniments were composed in the 19th century with the piano and its technical abilities in mind – such as volume change and sustaining pedals – declaring any claims at authenticity totally bogus. One would have to recompose the accompaniment to make that possible, at the very least cutting out some of the very low notes or doubling which would have been impractical in the Baroque era.

Appropriate singing style in Durante’s Danza, Danza Fanciulla

As for the singer, do they attempt vibrato-less baroque-style singing of limited volume and dramatic expression? Many modern recordings use Baroque-style re-orchestrations. These charming pastiche versions have their own validity, but they are stylistic anachronisms. Dmitri Hvorostovsky – winner of the 1989 Cardiff Singer of the World competition – is one of the leading operatic baritones of his generation. His Aria Antiche album was one of his biggest hits. The accompaniments on this CD are all modern orchestrations, and are certainly effective. But they are nonetheless a 20th century “imagining” of 19th century Baroque style. As for “barihunk” Dmitri: his vocal swagger – impressive as it may be – is probably very far removed from what singers in the Baroque era would have sounded like. The full-throated chest voice is an invention of the romantic era just as surely as the media invention of the barihunk is a 21st century phenomenon. In all likelyhood Danza, danza fanciulla would have been sung by a decidedly unvirile castrato. Given the church’s prohibition on women singing in church, Durante would no doubt have had a stable of castrated boys at his diposal to sing his sacred works. This song was very probably composed for one of these children unfortunately cursed with musical talent.

As for the singer, do they attempt vibrato-less baroque-style singing of limited volume and dramatic expression? Many modern recordings use Baroque-style re-orchestrations. These charming pastiche versions have their own validity, but they are stylistic anachronisms. Dmitri Hvorostovsky – winner of the 1989 Cardiff Singer of the World competition – is one of the leading operatic baritones of his generation. His Aria Antiche album was one of his biggest hits. The accompaniments on this CD are all modern orchestrations, and are certainly effective. But they are nonetheless a 20th century “imagining” of 19th century Baroque style. As for “barihunk” Dmitri: his vocal swagger – impressive as it may be – is probably very far removed from what singers in the Baroque era would have sounded like. The full-throated chest voice is an invention of the romantic era just as surely as the media invention of the barihunk is a 21st century phenomenon. In all likelyhood Danza, danza fanciulla would have been sung by a decidedly unvirile castrato. Given the church’s prohibition on women singing in church, Durante would no doubt have had a stable of castrated boys at his diposal to sing his sacred works. This song was very probably composed for one of these children unfortunately cursed with musical talent.

Click here to listen to Dmitri Hvorostovsky singing Durante’s Danza, danza fanciulla.

Click here to listen to Christiaan d’Hooghe – a countenor – the closest thing we have today to a Castrato sound – singing Durante’s other famous Aria Antiche Vergin Tutto amor.

Restoration versus recreation

Questions facing performers of this type of work is similar to those facing art historians when dealing with the prospect of restoring works from the past. The recent restoration of the Sistine Chapel is very controversial. The results of the cleaning were quite extreme. The colours that emerged after the restoration were quite startlingly different from what we had become accustomed to. Colours were surprisingly bright. Some might even say garish and gaudy. Our picture of the enchanting rotund angels floating in clouds of light pink, has changed dramatically and many books on the art of Michelangelo have had to be revised, some even rewritten.

As always, the experts are divided on the results.

The interesting part is that this modern restoration attempt was not the first. Already in 1625, a restoration was carried out by Simone Lagi, the Vatican’s “resident gilder”, who wiped the ceiling with linen cloths and cleaned it by rubbing it with bread. He occasionally resorted to wetting the bread to remove the more stubborn accretions. His report states that the frescoes “were returned to their previous beauty without receiving any harm”. Lagi also applied layers of glue-varnish to revive the colours. Between 1710 and 1713 a further restoration was carried out by the painter Annibale Mazzuoli and his son. They used sponges dipped in Greek wine (with a very high acidity similar to vinegar) which was necessitated by the accretion of grime caused by soot and dirt trapped in the oily deposits of the previous restoration. Mazzuoli then worked over the ceiling, according to an “eye-witness report” (by now almost 300 years old) to deliberately strengthen the contrasts by over-painting details. They also repainted some areas the colours of which were lost because of the efflorescence of salts caused by the salpetre leaks from the roof above the ceiling. So, to be fair, we have absolutely no way of telling if the recent renovations restores the Sistine Chapel to its original state as Michelangelo conceived it, or if it has been restored to the sate in which it was left are being cleaned with wet bread, or after parts had been repainted by Annibale Mazzuoli.

Another equally startling restoration of Baroque fresco-painting is the restored paintings of Flemish Master Paul Bril in the San Silvestro Chapel at Rome’s Sancta Sanctorium. Bril’s work has only seriously entered the conscious realm of art-historian endeavour since this project revealed the extent of his achievement. Funded by the John Paul Getty Foundation, over 1.700 square meters of wall space was restored by forty art restorers and experts. Project leader Maurizio De Luca, who also oversaw the recent restoration of the Pauline Chapel by Michelangelo inside the Vatican, sates confidently: “Like any good restoration, it is invisible.”

Some might beg to differ.

Technically it was a stunningly complex restoration process: deep fissures risked bringing down whole patches of painted ceiling plaster, and inside the chapel with its high, vaulted ceiling the painted walls and ceiling were literally obliterated by four centuries of accumulated candle grease and grime. Only the faintest traces of the paintings remained, and all colors and themes were literally lost to time, and hence forgotten. The restorers painstakingly removed one layer of dirt, then waited to see the result before tackling the next.

The results are rather startling. The colours are extremely bright and direct. If this is what Baroque frescoes really looked like, who is to say we don’t also have the wrong idea of how Baroque music is supposed to have sounded?

My task as coach and accompanist for this “Aria Antiche” is therefore not so simple. There are no hard-and-fast rules. Recreating a supposed baroque-style is not possible: the instrument I play is a 9 foot concert grand piano made of steel and wood, not a delicate little spinet. To attempt to play the piece in a technically “clean” manner, sheared of rubato and other agogic responses accumulated in subsequent centuries – to the text as well as the harmonies – would seem perverse: like washing the original in vinegar. By the same token, I feel that simply following the romantic indications – not to mention the thick octaves and large chords in the accompaniment – is the equivalent of centuries’ worth of accumulated oil, soot and grime. I am not sure I am in the market for recomposing the accompaniment, to attemtp a compromise. Not yet, anyway.

In preparing a performance I shall attempt neither to wash the original with wet bread nor vinegar. The key – of course – is the singer. This work will be sung by Violina Angeulov, a superb mezzo-soprano trained at the UCT Opera School by Sarita Stern. As we work on the programme in the next couple of weeks, I am sure we shall do our own restoration and recreation of “Danza, danza fanciulla”. We have no idea what we might yet discover. Perhaps we will dance to Durante’s tune. Or perhaps we won’t. We might just dance our own dance, to the sounds carried on the wind down through the centuries. And how we dance, depends entirely on what we choose to hear. And who knows which voices will be whispering in our ears?

Violina Anguelov (mezzo-soprano) CV

Violina was born in Bulgaria. She obtained her Performer’s Diploma in Opera with distinction as well as Honours Degree in Singing (First Class) from the University of Cape Town under voice teacher Sarita Stern. She has been awarded the Adcock Ingram Music Prize, the Leonard Hall Memorial Prize and Erik Chisholm Prize.

She made her European operatic début as Dorabella in Cosi fan Tutte in Hanover, Germany, in 2000. Her South African operatic début was as Cherubino in The Marriage of Figaro with Cape Town Opera in 1999. Since then she has sung, just to mention a few, roles such as Zerlina in Don Giovanni, Rosina in The Barber of Seville, Fenena in Nabucco, Marguerite in Berlioz’s La Damnation de Faust, Ruggiero in Alcina, Nerone in L’Incoronazione di Poppea, Hänsel in Hänsel and Gretel, Idamante in Idomeneo, Orlofski in Die Fledermaus, Mrs. Roland in the One Act One Woman opera Dark sonnet by Erik Chisholm in celebration of 100 years of the composers birth, Elisetta in Il Matrimonio Segreto at the Pretoria State Theatre. She has been invited twice to perform for Opera Africa in the roles of, Romeo in I Capuleti e I Montecchi by Bellini performed in Pretoria State Theatre and Amneris in Aida by Verdi performed both in the Pretoria State Theatre and Johanneburg Civic Theatre. She also sang the as Third Lady in Mozart’s Magic Flute a production directed by William Kentridge. This production was performed in Cape Town Opera House and Civic Theatre Johannesburg. Her latest appearances include the roles of Suzuki in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly and Mrs Patrick De Rocher in Jake Heggie’s opera Dead Man Walking both productions of Cape Town Opera.

She has a vast repertoire of sacred works: Coronation Mass by Mozart, Stabat Mater by Pergolesi, Gloria by Vivaldi, St. Theresa Mass by Haydn, Mozart’s Requiem, Handel’s Messiah, The Dream of Gerontius by Elgar, Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis and 9th Symphony, Bach’s Easter Oratorio as well as St. Johan’s and St. Matthews Passions, L’Enfance du Christ by Berlioz, Elijah by Mendelssohn and Verdi Requiem. She has worked with conductors such as: Doctor Barry Smith, Arnold Bosman, Chris Dowdeswell, Doctor Donald Hunt, Richard Cock and Kamal Khan.

My Blog has moved to www.albertcombrink.com

The arranged folksong is a bit like a precious stone, taken by a well-known composer and reset in a new setting, both creating an opportunity to view the well-known gem afresh, but also to create a new piece all-together. Benjamin Britten’s folksongs vary from simple re-arrangements to virtually brand new art-songs. I will be performing a selection of these in a programme called Sweeter than Roses, and other upcoming concerts.

Benjamin Britten

The first set was written during the self-imposed exile of Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears – as conscientious objectors to the British War effort as well as the legal intolerance of homosexual partnerships – to the USA from 1932 to 1942. Published in 1943 these works therefore also reflect a certain nostalgia for the homeland of a composer in exile. Benjamin Britten (Lord Britten of Aldeburgh 1913-1976) needed recital and encore material for his recitals with England’s foremost tenor of the time, his life-partner Sir Peter Pears (1910-1986). By 1947, three sets of folksongs from the British Isles and mainland Europe were published, forming a treasure trove of recital material. Written with piano accompaniment, a few were orchestrated in the early 1950’s.

Folksong setting in Britain prior to Britten

Britten’s English folksong publication is predated by a massive project during the 1780’s by George Thomson Edinburgh (1757-1851), of publishing arrangements of folksongs by the greatest European composers. Thomson recruited no less than Joseph Haydn and Ludwig von Beethoven, Hummel and Carl Maria von Weber. The British public seemed to enjoy the prestige of these names, and there was an absolute boom in sales and interest in dressing up folkmusic in “civilised garb”.

Cecil Sharp (1859-1924) was another important figure in the history of English Folksong, collecting over 4000 folksongs and notating each by hand. He published 1, 118 folk melodies and wrote over 500 accompaniments. By all accounts he was not much of a composer, and his accompaniments and folksong settings are rather dull, but they are extremely valuable in the preservation of the vocal lines. According the Graham Johnson, veteran accompanist and close friend of Peter Pears in his last years, Cecil Sharp prided himself on the “unobtrusive” nature of his accompaniments, claiming that they added to the authenticity of his legacy.

Grainger's "Free Music Machine"

Australian pianist and composer Percy Grainger (1882-1961) came to Britain in 1901, using a recording machine. Britten got to know these recordings, conducting and recording “Salute to Percy Grainger” in the 1970’s for the Decca record Label. Grainger’s folksong transcriptions differ radically from his folksong arrangements, in that they are meticulously notated, often with highly complex metres and rhythmic patterns, as the young man strove to write down the performance he heard as accurately as possible.

Britten’s Folksongs

Britten was content to use the material collected by others. His songs are not meant for the ethnomusicologist or anthropologist. They are designed for a collector and analyst of a very different nature: the recitalist. Many writers have bemoaned the “artyness” of Britten’s folksong settings. They were specifically intended as encores and to end the Britten-Pears recitals.

Some musical characteristics of Britten’s folksong settings.

Britten was a great Schubert interpreter. The Britten/Pears Schöne Müllerin is a joy to hear. I am in awe of Britten’s control and fine sense of nuance in this performance in particular, but the entire Britten/Pears Schubert legacy is a treasure. As a performer, I sense something Schubertian in the folksong settings. As with some of Schubert’s accompaniments the piano parts are often based on a single motif or pianistic “idea” without too much development. The strophic nature of the songs lend themselves to a comparison with Die Schöne Müllerin . The beauty of the Britten settings is the simplicity but highly effective nature of the accompaniments, to reveal, introduce and weave the mood of the song. Britten’s experience as an opera composer comes into play in the more narrative songs, where dramatic scenes are spun with utmost efficiency.

I won’t be discussing all the folksongs in the settings here, but some that I am preparing for current concerts.

Down By The Salley Gardens (W. B Yeats) 1889

Down by the salley gardens my love and I did meet;

She passed the salley gardens with little snow-white feet.

She bid me take love easy, as the leaves grow on the tree;

But I, being young and foolish, with her did not agree.

In a field by the river my love and I did stand,

And on my leaning shoulder she laid her snow-white hand.

She bid me take life easy, as the grass grows on the weirs;

But I was young and foolish, and now am full of tears.

Salley Gardens where the lovers did meet

The Salley Gardens

Ironically, the first folksong isn’t really a folksong. Unhelpfully, Britten subtitles the song as “Irish Tune”. The text is by William Butler Yeats (1865-1939), Irish poet and dramatist and one of the greatest poets in the English language of the twentieth century. He was a leader of the “Irish Renaissance” and spiritualist, winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1923. It was published in 1889 in “The Wanderings of Oisin and Other Poems”.

Yeats indicated in a note that it was “an attempt to reconstruct an old song from three lines imperfectly remembered by an old peasant woman in the village of Ballisodare, Sligo, who often sings them to herself.” Yeats’s original title, “An Old Song Re-Sung”, reflected this; it first appeared under its present title when it was reprinted in Poems in 1895

The melody is by Northern Irish Composer Herbert Hughes, whose Down by the Sally Gardens was published in 1909 in “Irish Country Songs Vol. 1”, who originally used the text by Yeats. True, his accompaniment is clumsy and fussy, but he created the essence of the song. Britten’s “resetting” gives us the opportunity to appreciate the gem in all it’s glory.

All through The Sally Gardens the accompaniment suggests the slow falling of tears and – you will notice this at once when you hear the song – the introduction, at the start, of a note contradicting the key is a masterly touch. The gentle throb of the quaver pattern is broken by a sad little figure, but follows the natural rhythm of Yeats’ poem perfectly. A song both static and somehow “suspended” in time, a moment of reflection captured in space and time, this is a truly remarkable creation. A very effective “flattening” of the harmony on the final “young and foolish” is an expressive masterstroke of a composer acutely attuned to the mood and emotion of the text. The tiny postlude sums up the sadness of an older protagonist who remembers his/her own youth and the loss of love.

The Latin name for the Weeping Willow is the Salix, and willows are sometimes referred to in poetry as “weeping Salleys”. The Irish name for a willow is “Saileach”. “Salley Gardens” then could refer to a secluded willow grove where lover’s could tryst in secret and seclusion.

The Ashgrove – the version of the text set by Britten

Down yonder green valley where streamlets meander

When twilight is fading I pensively rove.

Or at the bright noontide in solitude wander

Amid the dark shades of the lonely ash grove.

Twas there while the blackbird was cheerfully singing

I first met that dear one, the joy of my heart.

Around us for gladness the bluebells were ringing

Ah! then little thought I how soon we should part.

Still glows the bright sunshine o’er valley and mountain,

Still warbles the blackbird its note from the tree;

Still trembles the moonbeam on streamlet and fountain,

But what are the beauties of Nature to me?

With sorrow, deep sorrow, my heart] is laden,

All day I go mourning in search of my love!

Ye echoes! oh tell me, where is the sweet maiden [loved one]?

“She [He] sleeps ‘neath the green turf down by the Ash Grove.”

Ashgrove in Winter

The Ashgrove

Subtitled “Welsh Tune”, the first published version of the tune was in 1802 in the book “The Bardic Museum” by harpist Edward Jones.. Telling of a sailor’s love of “Gwen of Lynn”, a similar tune appears in “The Beggar’s Opera” by John Gay (1728) in the song “Cease your Funning.”

Britten here moves away from simple “Folksong setting” or Schubertian “artistry”, experimenting with harmonies and canons and passages in varied imitation. The bluebells “chime” almost literally in the piano part. A little Messianic bluebird triplet ruffles the feathers of traditional folksong collectors and various harmonic shifts, reflect an unstable mind. The simple tune belies the tragedy of the text, and Britten’s miniature mad-scene is filled with tremendous empathy for the suffering of the mourning lover.

O Waly, Waly – The text as set by Britten

The water is wide, I cannot cross o’er,

But Neither have I the wings to fly.

Give me a boat, that can carry two,

And both shall row, my love and I.

I leaned my back up against an oak

I thought it was a trusty tree

but first it bent and then it broke

And so my love did unto me.

A ship there is and she sails the sea,

She’s loaded deep as deep can be,

But not so deep as the love I’m in

I know not if I sink or swim.

O love is handsome and love is fine

And love’s a jewel when it is new

but love grows old and waxes cold

And fades away like morning dew.

O Waly, Waly

O Waly, Waly

The inherent challenges of love are made apparent in the narrator’s imagery: “Love is handsome, love is kind” during the novel honeymoon phase of any relationship. However, as time progresses, “love grows old, and waxes cold”. Even true love, the narrator admits, can “fade away like morning dew”

Britten here uses the tune as transcribed by Cecil Sharp on his trip to America during World War 1. It is thought to be a Scottish or English Folksong. Britten creates a sparse accompaniment allowing the voice to float free. A gentle barcarolle rhythm in the accompaniment sets the watery scene that rocks with a gentle ebb and flow. The harmonies in the accompany change, but very slowly, gently. The subtle changes makes this song a hypnotic masterpiece. Powerful but understated discords such as the one on the word “cold” create new meanings in the text. In one chord, the disintegration of a relationship is expressed, summed up, wrapped up in a flattened seventh at once comforting as symbolic of the death of love.

Down By The Salley Gardens: Some Recorded Materials

Tenor John McCormack performing an arrangement not by Britten. I enjoy his “folk” accent and the glimpse into the past provided by the scratchiness of the old record.

Countertenor Andreas Scholl performing (in the studio in 2001) an arrangement for voice and string orchestra. While the strings add the rustling of the trees of the “Salley Gardens” I do miss the simplicity of Britten.

Nicolai Gedda and Gerald Moore, another great Schubertian pianist, give a rather “recitalish” performance. However, Gedda, whose range of recording and performance simply continues to amaze me for its sheer breadth and depth, displays admirable sensitiveity to the text.

Irish folk duo Lark and Spur sing a charming popular celtic version.

The Ashgrove: Some Recorded Materials

Nana Mouskouri with two guitarists accompanying.

These original Welsh words tell a violent, bitter tale. A young heiress falls in love, to the dismay and rage of her powerful father and lord of the region. He means to kill her lover, but kills her by chance, and she prefers death to being an unloved prisoner at Ash Grove Palace. It is sung here in Welsh by Llwyn Onn as Dafydd o Fargoed. The accompaniment is based on Benjamin Britten’s arrangement from 1943 set then to gentle English words of mourning for a dead lover.

O Waly, Waly: Some Recorded Materials

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears give the autoratitive version. The pathos and pianissimo of the final verse is breathtaking.

A modern tenor version by American tenor Gregory Kunde. The pianist is not credited in this live 1998 perfromance.

Sir Thomas Allen sings an unaccompanied version at the Northumbrian seashore. The seagulls in the background form a touching accompaniment to a tune of great power.

At the other end of the spectrum is Bob Dylan in a live 1975 version.

The beautiful and always sensitive Eva Cassidy sings a touching version I would not want to be without.

The Foggy, Foggy Dew: Some Recorded Materials

Tenor Steve Davislim and pianist Simone Young perform the Britten arrangement of folksong ‘Foggy, Foggy Dew’ and speak about thier approach to presenting this piece. From ‘Benjamin Britten Folksong Arrangements’, MR301120 Melba Recordings SACD.

Sinead O’Connor and the Chieftains sing the Irish republican song “The Foggy Dew”.

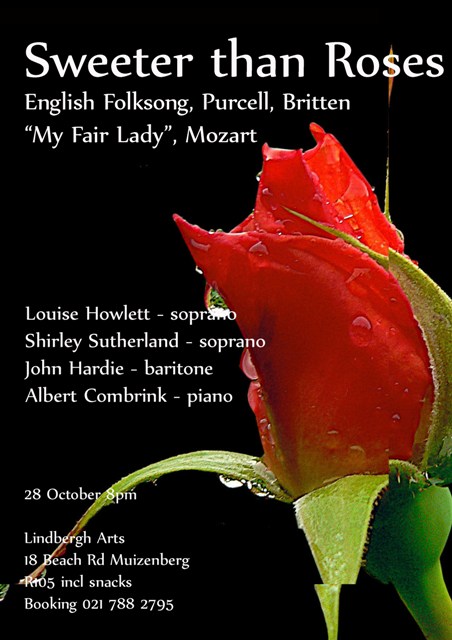

I will be performing these and other Britten folksong settings in concerts over the next few months. One of these features singers Louise Howlett, Shirley Sutherland and John Hardie, accompanied by Albert Combrink. Also on the programme is “Sweeter than roses” and other Britten realisations of Purcell songs, and extracts from that delightful Rose seller Eliza Doolitle from “My Fair Lady”, and some operatic roses such the one one Carmen throws at at Jose, intoxicated with love.

“Sweeter than Roses”

– English and Italian songs of the joys of love by

Purcell, Britten, Mozart, Sondheim incl. “My Fair Lady”

This delightful programme of mostly English songs explores the joys and dreams of young lovers through the songs of Purcell (“If music be the food of love”), Britten’s famous Folksong settings (“The Foggy, foggy dew”) and operatic extracts by Mozart, that master of comic characterisation. The three singers are all noted for their variety and can perform in different styles. Shirley Sutherland will lead the second half of the programme with extracts from “My Fair Lady”, the show in which she had a major triumph at the Artscape Theatre in 2008. Louise Howlett, a veteran stage performer, will include extracts from her soon-to-be released second CD from the musicals “Cats” and “A Little Night Music”. Baritone John Hardie – winner of various awards such as the Leonard Hall Memorial Prize – is the perfect foil for the two ladies. He will be the Figaro to their Suzanna and Cherubino and the Don Giovanni to their Zerlinas. The programme will reflect the more playful aspect of young love, from the charm and beauty of setting of Shakespeare to more contemporary and popular music. The fact that most of the songs are in English makes this a programme with instant appeal for audiences of all ages. The keyword is variety, and versatility is what this set of performers are known for.

Lindbergh Arts Foundations – 18 Beach Road, Muizenberg

R105 Including Snacks

Booking 021 788 2795

Louise Howlett (Soprano)

Louise Howlett, originally from England, studied at the Royal College of Music in London, with Margaret Cable where she featured in a number of competitions and masterclasses. As a member of the National Youth Music Theatre, Louise toured to the Bergen Festival and Edinburgh Main and Fringe Festivals, aswell as performing in the award winning production of The Ragged Child at the Sadlers Wells Theatre, London. She performed in television productions of both The Ragged Child and the opera of The Tailor of Gloucester.

Louise came to South Africa in 1993 to work as Organiser for the National Chamber Orchestra in the North West Province, and soon decided to make South Africa her home. She sang on many occasions with the NCO including a number of corporate functions in Sun City and Johannesburg. She also performed in a number of Oratoria including Nelson Mass, The Messiah and Vivaldi’s Gloria, and was involved in choral training workshops and master classes. In March 1999 she moved to Cape Town where she is now based. Her Cape Town debut took place with the Cape Town Philharmonic Orchestra at their Kirstenbosch Millennium Concert; but her love of jazz and the musicals led her to create her own unique combination of classical, broadway and jazz “Across the Styles” projects out of which her “Serenade” series was born. These productions can vary from classical versions, to jazz standard evenings to the full range of genres blended into one programme. She has performed with great success at various venues and festivals including the Kirstenbosch Winter Chamber Music Series, the Greyton Rose Festival, and most recently at the Baxter Theatre.

Louise is a regular presenter on Fine Music Radio. Her programme “For the Love of Opera” features all the latest news and reviews of opera around the world today.

John Hardie (Baritone)

John studied singing at UCT and Stellenbosch University and his teachers include Sarita Stern, Nellie du Toit and Marita Napier. He sang with Capab Opera for 3 years taking part in productions of “Albert Herring” and “Cosi fan Tutte”. He won the College of Music Opera prize in 1988 and 1989, the Friends of the Nico Malan Opera Prize in 1990, the Leonard Hall memorial Prize in 1991. He has performed professionally with accompanists such s ALbie van Schalkwyk, Tommy Rajna and Neil Solomon.

SHIRLEY SUTHERLAND – Coloratura Soprano

Shirley Sutherland graduated from UCT with an Honours degree in Music under Sarita Stern and Angelo Gobbato. She has also completed a National Higher Diploma in Opera (Cum Laude) at the Pretoria Technikon Opera School under the tutelage of Eric Muller.

Her ability to sing such a varied repertoire of music being Opera, Operetta, Broadway, Classical contemporary, light classical has found her performing to diverse audiences locally and abroad.

Her many operatic roles include that of Tytania in Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Adele in Die Fledermaus, Hanna in Lehar’s The Merry Widow, Pamina in Mozart’s Magic Flute, Micaela and Frasquita in Bizet’s Carmen, Lucy in Menotti’s The Telephone Madame Mademoiselle Warblewell in Mozart’s The Impresario and as well as Dvorak’s Rusalka which she performed in Sweden. Her many musical roles include that of Eliza from My Fair Lady, Magnolia from Showboat which was performed in Germany, Julie in The Carousel, Mabel in The Pirates of Penzance, Meg in Brigadoon and Roxie in Chicago for which she received the Cape Times Award for the best leading lady in a musical. She has sung Gabriel in Haydn’s Oratorio The Creation and performed in Mozart’s Coronation Mass with the Johannesburg Symphony Orchestra.

She has been part of the Pretoria based Black Tie-Ensemble with Mimi Coertse and part of Cape Town’s Opera Studio.

Shirley is in great demand as a soloist and also teaches part-time at schools in the Cape area.

Albert Combrink (Piano)

Albert, currently a freelance pianist, completed his MMUS in Piano Performance from Natal University under Isabella Stengel, as well as three UNISA Licentiates: Piano Performance, Piano Accompaniment and Teaching (Cum Laude). He made his concerto debut with the NPO at 18. Since then he has performed regularly at major centres throughout the country, as soloist and accompanist, in both classical and popular music fields. He was finalist in the ATKV Music Competition and winner of the Young Natal Chamber Competition and UND Performer’s and Composer’s competitions after which he was commissioned to write to the first Afrikaans Catholic Mass. He has extensive recording experience, including Hindemith’s Piano Concerto “Four Temperaments” with the NPO and David Tidboald, through radio and television broadcasts (including BBC World) to the recent CPO recordings of works by Hofmeyr and Schnittke. He was repetiteur for the UCT Opera School as well as Cape Town Opera, performing also as orchestral pianist and harpsichordist in operatic productions. His operatic experience with CPO included “Showboat” and “Porgy and Bess” which toured Sweden and Germany. He has acted and recorded for the eTv show “Backstage” and “Stokvel” and been involved in various film projects. As member of the Cape Town Tango Ensemble he has performed at all the major festivals in the country, with performers such as Mark Hoeben and Ina Wichterich. His Tango CD featured in the film “Tango Club”. He has worked with directors such as Janice Honeyman, Jaco Bouwer and Marthinus Basson. He is vocal coach for Portabello, whose production of Mozart’s “Magic Flute” won a London Critics’ “Olivier Award” in 2008, and has toured Ireland, Japan and Singapore. He has also been Music Director and Assistant MD for various productions including the New Space Theatre’s production of Sondheim’s “Assassins” which won two Fleur du Cap Awards. He is co-author of 3 Arts & Culture Textbooks which have sold over 150 000 copies.

Ständchen by Richard Strauss: Passion and Seduction in the Garden of Eden

September 12, 2009

My Blog has moved to www.albertcombrink.com

The rustling and shimmering of the piano part which opens Strauss’ song Ständchen – which I should perhaps be practising for tomorrow’s concert, rather than writing about it – is one of those startling inventions by this composer that simply hooks the listener from the first note. The song tells the charming story of a secret lover’s tryst in the dark of night, the beloved ardently seduced into sneaking into the forest for a night of passion. Strauss responds to the vividly descriptive words with a song filled with passion and seduction.

Strauss composed his Sechs Lieder Op.17 to poems by Adolf Friedrich von Schack between 1885 and 1887. At that time Strauss was the court music director in Meiningen and moved to Munich to become the Court Opera’s third conductor. Strauss’ early experience in the opera house not only stood him in good stead as an opera composer, but his songs often have an operatic sweep about them, and a clear sense of climax and dramatic pacing.

Strauss’ music brings to life the expectation and excitement of the clandestine tryst of Schack’s poem.

Ständchen by Adolf Friedrich, Graf von Schack (1855-1894)

Mach auf, mach auf, doch leise mein Kind,

Um keinen vom Schlummer zu wecken.

Kaum murmelt der Bach, kaum zittert im Wind

Ein Blatt an den Büschen und Hecken.

Drum leise, mein Mädchen, daß [nichts sich]1 regt,

Nur leise die Hand auf die Klinke gelegt.

Mit Tritten, wie Tritte der Elfen so sacht,

[Die über die Blumen]2 hüpfen,

Flieg leicht hinaus in die Mondscheinnacht,

[Zu]3 mir in den Garten zu schlüpfen.

Rings schlummern die Blüten am rieselnden Bach

Und duften im Schlaf, nur die Liebe ist wach.

Sitz nieder, hier dämmert’s geheimnisvoll

Unter den Lindenbäumen,

Die Nachtigall uns zu Häupten soll

Von unseren Küssen träumen,

Und die Rose, wenn sie am Morgen erwacht,

Hoch glühn von den Wonnenschauern der Nacht..

Ständchen in free translation by Albert Combrink

“Love Song”

Open up, open up, but softly my child,

So as not to wake anyone from their sleep,

The stream is barely murmuring, the wind hardly causes quivers

In a leaf on bush or hedge.

So, softly, my young girl, so that nothing stirs,

Just lay your hand softly on the door-latch.

With steps as soft as the footsteps of elves,

that hop over the flowers,

Fly lightly out into the moonlit night,

Sneak to me in the garden.

Around us sleeps the blossoms along the trickling stream,

Fragrant in sleep, only love is awake.

Sit down, here it darkens mysteriously

Beneath the linden trees,

The nightingale over our heads

Shall dream of our kisses,

And the rose, when it wakes in the morning,

Shall glow from the joyous showers of the night.

"Lovers in the garden" Paul Gustave Dore (1832-1883)

Early in his career Strauss was obviously taken with the poems of Von Schack – the son of a wealthy landowner – setting 16 of his poems in the songs which comprise his Opus 15, 17 and 19 sets, completed by the age of 24. As with most of Strauss’ choice of poets, Schack might not be regarded as a towering figure in the poetic landscape, so to speak. Yet his poems provide much suggestive imagery to stimulate the imagination – especially one as creative as Strauss. Schack’s moonlit forest shakes, trembles, quakes and quivers and in the morning the roses will be glowing form the night’s “Wonnenschauern” – a virtually untranslatable portmanteau suggesting the “joyous showers” of the night’s activities (perhaps one would be wise not to interpret it only literally). The grammar of the poem makes it hard to distinguish whether the poet is taking the beloved into the night, or merely singing a song of seduction and describing the delights that await them – as the title suggests. The music however, tells a fuller story.

Tonality is vitally important in the music of Strauss and he adhered loosely to a set of tonal symbols. C major is often regarded as his “Key of Creation”, of elemental power, the source of the Big Bang: note for example the opening of Also Sprach Zarathustra or the song Zueignung (Op. 10 No.1) – both powerful existential statements. A flat major is used for pious religious expressions such as those of John the Baptist in the opera Salome. Ständchen is in F Sharp major, a key it only shares with a single other song from his 205: Traum durch die Dämmerung. This is also the key of love at first sight in the “Presentation of the Rose” duet from Der Rosenkavalier. Often associated with love, dreaminess and intoxication, this key suggests two lovers “high” on love, the romance of the moment and the beauty of the surroundings.

The house near the forest - anon.

Musically the first two verses are repeated verbatim. Verse one lures the beloved out the door. Verse two lures the beloved into the darkness of the Linden trees. Octave leaps, like an ardent but secret call and long passages in the same key suggest so beautifully the furtive seduction. The piano quakes and quivers in excitement and but also surrounds the voice in the night-sounds of the forest: the trembling, rustling and positively quaking leaves and the murmuring trickle of the ever-flowing but never dangerous stream. The excited frisson in the hearts of the lovers is expressed in the darting of the piano part. The figuration is more pianistic than it appears at first sight: The 4th finger falls naturally on the black notes and the short 5th finger feels comfortably in place on the adjacent white finger, making the rippling pianissimo a joy to play. Yet some sharp-shooters’ aim is required when the modulations move in between the black notes.

Verse three gets down to the serious business of love-making. As the beloved is invited to “sink down” on the soft grass, the piano part sinks gently down to the key of D Major, the key of nature: Daphne in the garden; the garden of the “Vier Letzte Lieder. The flattened VI key is such a quintessentially Romantic musical symbol for the mysterious and the magical. Another magical use of the flattened sixth key occurs in Schubert’s rapturous Nacht und Träume (Night and Dreams, D. 827) of 1822, where the joy of the dreamers is expressed with breathtaking tenderness.

The piano part of the third verse reveals some fussiness on the part of the composer. The little figurations, while remaining true to the original idea, change shape and inversions a few too many times, making it unnecessarily awkward for the pianist. I wonder if some have not cheated the odd beat or two. It is mainly pianissimo and the pedal hides a multitude of sins. As the piano part modulates downwards to B Major, the voice starts its ecstatic ascent to the climax, Strauss finding it necessary to repeat the words “Hoch glühn” (glowing on high) to sustain the excitement and extend the exquisite consummation.

Linden Tress abound in German Lieder

At this point there is a discrepancy between the piano-accompanied version of the song, and the orchestral arrangement of the song. In the orchestral version the high A sharp of the climax is held double the length. It is a glorious effect. I have heard various sopranos take the “long cut” in the piano version, with the pianist either left high and dry at the barline, or, in the case of some conductor-pianists such as Wolfgang Swallisch and Sir Georg Solti, they reversed the process of orchestration and rewrote the piano part, adding extra bars as per the orchestral version. The orchestral version also ends more abruptly, leaving out the piano’s brief but charming postlude.

Strauss only wrote 15 of his 205 songs expressly for Voice and Orchestra. He himself orchestrated 25 of the piano accompaniments and sanctioned some by others. These orchestrations were done at various times in his career, often to provide concert material for his wife Pauline de Ahna and some of the various sopranos with whom he travelled after Pauline’s career started winding down, such as the creator of the title role in Arabella, Viorica Ursuleac whom Strauss called “die treueste aller Treuen” (“the most faithful of all the faithful”).

Some recordings:

Walter Gieseking made a beautiful transcription of the song for solo piano. His own performance is unhurried and tender, a beautiful version giving a distilled ‘gestalt’, when the visceral excitement generated by a voice, is absent. FREE SHEET MUSIC of Gieseking’s transcription of Ständchen is available.

An opera singer more famous for his Puccini than his Strauss, Jussi Björling’s Bel Canto brings a wonderful line to this song, in an orchestral version.

Lotte Lehman (recorded here in 1941) remains an authority in this repertoire, having performed many times with Strauss himself.

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, the Über-Guru of Lieder, performs here with his main collaborator in the autumn-years of his career – Hartmut Höll, piano. This is about as deffinitive as modern interpretations get.

Fritz Wunderlich, who performed so many of Strauss’ taxing tenor roles before his untimely death, here gives one of the performances of a lifetime, in an orchestral set of Strauss comprising: 1 Heimliche Auffforderung, 2 Ständchen and 3 Zueignung.

Nicolai Gedda perhaps does not strike one immediately as primarily a lieder singer, but much of career was built around recital repertoire. Hs version is beautifully youthful and tender.

Sir Georg Solti postively basks in the virtuosity of the piano part. Here he acompanies Kiri te Kanawa with whom he performed and recorded not only the piano and orchestral version of this song, but also recorded a glorious Vier Letzte Lieder.

While the sheer sweep and drama of many of Strauss’ songs have attracted many larger voices, two very different versions by two very different sopranos reveal how the material can translate well to either voice-type in the hands of an intelligent singer. The Wagnerian size of Birtgit Nilsson (accompanied by Janos Solyom – 1975) contrasts sharply with the lyric colloratura of Kathleen Battle (accompanied by Warren Jones – 1991) but both reveal different aspects of the beauty of this song.

Related material: Nacht und Träume by Franz Schubert

Renée Fleming and the Lucerne Festival Orchestra conducted by Claudio Abbado perform an unidentified orchstration in 2005.

A young Kiri te Kanawa and Richard Amner perform a radiant version at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden in 1978.

Unlike the Linden Tree, the “Tree of Lovers” in German literature, Ständchen is evergreen and beloved the world over.

Manuel de Falla: Siete canciones populares españolas (1914)

September 8, 2009

My Blog has moved to www.albertcombrink.com

Manuel de Falla (1876-1946): Siete canciones populares españolas (Seven Popular Spanish Songs) (1914)

Despite the undeniable “Spanishness” of most of de Falla’s music, this cycle of seven songs is one of the few to directly use pre-existing Spanish melodies. Written in Paris, toward the end of his seven-year stay, the songs have remained so popular as to have overshadowed most of his other vocal works. Their premiere occurred shortly after that of his opera La Vida breve. At the eve of a World War there is a certain naive quality to be found in these songs, a nostalgia for the folk-music of his homeland. An intense period of work produced a series of quasi-nationalist masterpieces. Incredibly the end of 1915 saw the first performances of both El amor brujo (a dance-work or “gitanería” in one act) and the tone poem (and piano concerto in all but name) Noches en los jardines de España.

| Spanish Text | Free translations by Albert Combrink | |

El Paño Moruno Al paño fino, en la tienda, una mancha le cayó; Por menos precio se vende, Porque perdió su valor. ¡Ay!(Gregorio Martinez 1881-1947) |

The Moorish Cloth On the fine cloth in the store a stain has fallen; It sells at a lesser price, because it has lost its value. Alas! |

|

Seguidilla Murciana Cualquiera que el tejado Tenga de vidrio, No debe tirar piedras Al del vecino. Arrieros semos; ¡Puede que en el camino Nos encontremos! Por tu mucha inconstancia Yo te comparo Con peseta que corre De mano en mano; Que al fin se borra, Y créyendola falsa ¡Nadie la toma! |

Seguidilla Murciana Who has a roof of glass should not throw stones to their neighbor's (roof). Let us be muleteers; It could be that on the road we will meet! For your great inconstancy, I compare you to a [coin] that runs from hand to hand; which finally blurs, and, believing it false, no one accepts! |

|

Asturiana Por ver si me consolaba, Arrime a un pino verde, Por ver si me consolaba. Por verme llorar, lloraba. Y el pino como era verde, Por verme llorar, lloraba. |

Asturian To see whether it would console me, I drew near a green pine, To see whether it would console me. Seeing me weep, it wept; And the pine, being green, seeing me weep, wept. |

|

Jota Dicen que no nos queremos Porque no nos ven hablar; A tu corazón y al mio Se lo pueden preguntar. Ya me despido de tí, De tu casa y tu ventana, Y aunque no quiera tu madre, Adiós, niña, hasta mañana. Aunque no quiera tu madre... |

Jota They say we don't love each other because they never see us talking But they only have to ask both your heart and mine. Now I bid you farewell your house and your window too and even ... your mother Farewell, my sweetheart until tomorrow. |

|

Nana Duérmete, niño, duerme, Duerme, mi alma, Duérmete, lucerito De la mañana. Naninta, nana, Naninta, nana. Duérmete, lucerito De la mañana. |

Nana Go to sleep, Child, sleep, Sleep, my soul, Go to sleep, little star Of the morning. Lulla-lullaby, Lulla-lullaby, Sleep, little star of the morning. |

|

Canción Por traidores, tus ojos, voy a enterrarlos; No sabes lo que cuesta, »Del aire« Niña, el mirarlos. »Madre a la orilla Madre« Dicen que no me quieres, Y a me has querido... Váyase lo ganado, »Del aire« Por lo perdido, »Madre a la orilla Madre« |

Song Because your eyes are traitors I will hide from them You don't know how painful it is to look at them. "Mother I feel worthless,Mother" They say they don't love me and yet once they did love me "Love has been lostin the air Mother all is lost It is lost Mother" |

|

Polo ¡Ay! Guardo una, ¡Ay! Guardo una, ¡Ay! ¡Guardo una pena en mi pecho, ¡Guardo una pena en mi pecho, ¡Ay! Que a nadie se la diré! Malhaya el amor, malhaya, Malhaya el amor, malhaya, ¡Ay! ¡Y quien me lo dió a entender! ¡Ay! |

Polo Ay! I keep a... (Ay!) I keep a... (Ay!) I keep a sorrow in my breast, I keep a sorrow in my breast (Ay!) that to no one will I tell. Wretched be love, wretched, Wretched be love, wretched, Ay! And he who gave me to understand it! Ay! (“Ay” can be translated as “alas” or as a cry of pain. In the context of this fiery song, “alas” is too mild an exclamation. Melismatic “Ay”s are a feature in Spanish gypsy-influenced cante hondo.) |

Musical Considerations

In the music of De Falla, the world of Flamenco is never far from the surface. His accompaniments are inspired by guitar-figuration and his melodic material full of the flattened intervals and embellishments of the Flamenco style. A performance trend that has yielded interesting fruits has been to apply Flamenco performance tradition on what has essentially been regarded as a mainstream classical tradition.

Picasso: "The Old Guitar Player" 1903 |

Jason O'Donnell: "Picasso's Old Guitar Player" 2003 |

1. Vocal Style:

Operatic Mezzo-Soprano Jennifer Larmore sings a very idiomatic and passionate rendition of “Cancion del amor dolido” from the Theatre/Dance work (often referred to as his “ballet” “El amor Brujo”. Listen to Jennifer Larmore HERE. Another astonishing recording in the classical vein is that by Leontyne Price, excerpts of which can be heard HERE. Her voice is clearly a soprano, yet her strong lower register and the “chest” sounds so useful in her portrayals of Verdi heroines, is here put to dramatic use. Yet, it is still broadly operatic in conception.

Compare that classical style of performance with that of Ginesa Ortega, a Flamenco Singer. Or the cantaora in this clip with Pierre Boulez. I have not found any recordings of the Siete canciones in the Flamenco style, but it is clear that the melodies use Flamenco inflections. Lullabies with tranquil melodic lines share the stage with more fiery outbursts. In particular, the dark fury of the 7th song Polo reflects the Spanish “Duende” or “gravitas” in its melismatic writing. De Falla was clear that the melismas were not to be executed as coloratura in Italian opera, but rather as “extensive vocal inflections” based on the flamenco style. (Martha Elliott: “Singing in Style: a giude to vocal performance practices” p.269)

2. Influences on the accompaniments:

– De Falla and Riccardo Vines

While not achieving the fame as performer of his fellow Spaniards Granados or Riccardo Vines, De Falla nonetheless had an excellent reputation as a performer. In Paris he performed in the salons alongside the likes of Debussy. Vines in particular premierred many of his piano works and encouraged him to stretch his creative palet beyond his own abilities. The piano parts of the Siete canciones are virtuosic and remarkably pianistic,

– De Falla and Garcia Lorca

De Falla was an excellent pianist and performed as soloist and acompanist. It appears that he played a bit of guitar as well. In the 1920’s he worked with playwright Frederico Garcia Lorca (1898-1936), acting as a mentor and guide to the writer’s musical aspirations. By all accounts he became quite an expert pianist and guitar player under de Falla’s guidance. They perhaps did not overtly “colloaborate” on projects, but it is clear that works such as Lorca’s Canciones Españolas Antiguas were not only fashioned along the model of De Falla’s Siete canciones, but that in fact De Falla was the overseer of the process which led to their completion. Lorca was firstly a pianist and appeared to have made arrangements for guitar later such as the 12 Canciones. Lorca and de Falla shared a deep love for Flamenco and in 1922 organised a festival of Flamenco’s “Dark and Deep Song”, the Cante Jondo at the Alhambra in Granada. Their musical relationship is explored on this Compact Disc Recording.

– De Falla and Andres Segovia

Siete cancioneswas composed for piano, but has been orchestrated and arranged for guitar accompaniment. Segovia brought the virtuosic abilities of the solo guitar to the attention of many composers of the day and comissioned many new works. Falla wrote a large number of guitar works for Segovia, and it appears that they collaborated on transcriptions. It is not clear if the Segovia transcription of the Siete cancioneswas done in collaboration with De Falla. What is clear however was that the guitar version was done much later. Guitar-like figurations abound in the piano part. Repeated tremolo-figures reminiscent of repeated plucking of the same string abound in the writing. Strummed chords are recreated in “apreggiated” figures. Repeated pedal notes reflect an imagined guitar.

A comparison of recorded versions of the different accompaniments

Here follows some links to Youtube of various recordings of this cycle all featuring famous Spanish Mezzo-Soprano Theresa Berganza.

| With original Piano version by De Falla | With Orchestral arrangement made by Luciano Berio | With Guitar – version by Segovia |

| Full Cycle with Gerald Moore Part 1 Part 2 |

5. Nana only Full Concert part 1 Full Concert part 2 Full Concert part 3 |

1. El Paño Moruno 2. Seguidilla Murciana 3. Asturiana 4. Jota 5. Nana 6. Canción 7. Polo |

| Theresa Berganza – Mezzo-Soprano Gerald Moore Piano London 1960 |

Theresa Berganza – Mezzo-Soprano Paris 1987 |

Theresa Berganza – Mezzo-Soprano Gabriel Estarellas – Guitar Edinburgh 1987 |

The following link is to Amazon.com, featuring a disc by South African Soprano Andrea Catzel, giving a beautiful and idiomatic performance of this cycle with Thomas Rajna on the piano. The site has MP3 samples of the music. Andrea Catzel sings Falla et al.

A free copy of the Sheet Music in the original key can be downloaded HERE. A transposition of the entire set up a whole tone, was published by Boosey & Hawkes.

Cape Town Soprano Filipa van Eck and myself will be performing songs from the cycle Siete canciones populares españolas in various upcoming recitals such as this one:

Lindbergh Arts Foundation – 18 Beach Road, Muizenberg

Thursday 17 September 2009

10.30 am

R50 including Tea and Refreshments

Bookings: 021 788 2795

Allerseelen (Richard Strauss)

September 8, 2009

My Blog has moved to www.albertcombrink.com

Sixty years after his death, the music of Richard Strauss (11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) remains loved and sung often, regarded as a gift to the voice. From his first Christmas song, written at the age of 6, to the final page of “Malven”, completed just after the “Vier Lezte Lieder”, over 200 songs reflect an ongoing love-affair with the voice. His operas reveal great lyrical gifts. The songs are performed often and have been sung by some of the greatest singers in history. “Allerseelen” forms part of a selection of Strauss songs Cape Town soprano Filipa van Eck and myself will be performing in various upcoming recitals .

“Allerseelen” op.10 no. 8 (Text by Hermann von Gilm zu Rosenegg (1812-1864)

Published in 1885 when Strauss was 21, but possibly written when he was as young as 18, this song forms part of an extra-ordinary set of songs mostly written by a man still in his teens.

“Allerseelen” aus “Letzte Blätter” – with free translation by Albert Combrink

Stell auf den Tisch die duftenden Reseden. Die letzten roten Astern trag herbei. Und laß uns wieder von der Liebe reden. Wie einst im Mai. – Place on the table, the fragrant heather. The last red Asters, draw them near. And let us again talk of love. As once in May.

Gib mir die Hand, daß ich sie heimlich drücke, Und wenn man’s sieht, mir ist es einerlei, Gib mir nur einen deiner süßen Blicke, Wie einst im Mai. – Give me your hand that I can give it a secret squeeze. And if anyone saw it, to me it would be neither here nor there. Just give me one of your sweet gazes. As once in May.

Es blüht und [funkelt] dufted heut auf jedem Grabe. Ein Tag im Jahr ist ja den Toten frei. Komm an mein Herz, daß ich dich wieder habe. Wie einst im Mai. – Today each grave blossoms and gives off fragrance. One day in the year the dead are free. Come to my heart, that I may have you again. As once in May.

“Allerseelen” – Some textual considerations:

When writing his operas, Strauss demanded the highest quality from librettists. His working relationship with Hugo von Hofmannsthal (1874-1929) is well-documented. Hofmannsthal and Strauss had debates, arguments, philosophical discussions and volumes of correspondence, revealing much about the way in which Strauss crafted the music to suit the drama. And in many cases, vice versa. Hofmannsthal wrote libretti for several of his operas, including Elektra (1909), Der Rosenkavalier (1911), Ariadne auf Naxos (1912, rev. 1916), Die Frau ohne Schatten (1919), Die ägyptische Helena (1927), and Arabella (1933). Yet in each case, the composer had a handin the making of the text. “Strauss the song-maker” had a very different approach. Strauss found pre-made texts, often of variable quality. Austrian civil servant Hermann von Gilm zu Rosenegg (1812-1864) is today mainly remembered for his poetry set by Strauss – “Zueignung” Op.10 No.1 and “Die Nacht” Op.10 No.3 being the other famous examples.

1. Religious context

The poet uses the context of a religious ceremony to express a deep love and passion, tapping into sub-conscious depths of feeling that transcends mere romantic love. This is an ancient ceremony, both mythical and mystical. The dead are remembered by their loved ones with flowers and candles on their graves. Sometimes the dead are even invited to participate in meals, with dishes set out for them on the family table. “Allerseelen” or “All Soul’s Day” (sometimes called the “Day of the Dead”) always falls on November 2 (November 3rd if the 2nd falls on a Sunday). It is a Roman Catholic day of remembrance for friends and loved ones who have passed away. This comes from the ancient Pagan Festival of the Dead, which celebrated the Pagan belief that the souls of the dead would return for a meal with the family. Candles in the window would guide the souls back home, and another place was set at the table. Children would come through the village, asking for food to be offered symbolically to the dead, which would then be donated to feed the hungry. The Feast of All Souls owes its beginning to seventh century monks who decided to offer the mass on the day after Pentecost for their deceased community members. In the late tenth century, the Benedictine monastery in Cluny chose to move their mass for their dead to November 2, the day after the Feast of all Saints. This custom spread: in the thirteenth century, Rome put the feast on the calendar of the entire Church. The date remained November 2 so that all in the Communion of the Saints might be celebrated together.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905) - "The Day of the Dead" (1859)

Initially many Protestant reformers rejected “Allerseelen” Day because of the Theology behind the fest – in particular the concept of Purgatory, and the idea that human intercession on a particular day could affect the welfare of a soul. Intercession from the living is believed to free souls from their sins and hasten entry into heaven. All Soul’s Day lives on today, particularly in Mexico, where All Hallows’ Eve, All Saint’s Day and All Soul’s Day are collectively observed as “Los Dias de los Muertos” (The Days of the Dead). First and foremost, the “Days of the Dead” is a time when families fondly remember the deceased. But it is also a time marked by festivities, including spectacular parades of skeletons and ghouls. In one notable tradition, revellers lead a mock funeral procession with a live person inside a coffin. Many customs are associated with “The Day of the Dead” celebrations. In the home an altar is made with an offering of food upon it. It is believed that the dead partake of the food in spirit and the living eat it later. The ofrendas (offerings) are beautifully arranged with flowers such as marigolds (zempasuchitl), which are the traditional flower of the dead. There is a candle placed for each dead soul, and they are adorned in some manner. Incense is also often used, and mementos, photos, and other remembrances of the dead also adorn the ofrenda. Other traditions and customs include visiting the graveyard for a picnic, decorating the relatives’ graves, lighting candles while reciting a prayer for each departed soul, and leaving doors and windows open on “All Soul’s Night”. The modern commercialism of Halowe’en reflects the concept of the souls being “free from restraint” on this particular night.

The speaker of the song addresses the loved one, using the framework of spiritual freedom as an allegory for the freedom of their love, either to relive itself “as it once did in May”, or perhaps free from social restraint – “If anyone saw me squeeze your hand, it would make no difference to me”.

Aster Pomplona

Aster Pomplona2. Flowers

Flower imagery abounds: The first stanza calls for the strongly scented blossom spikes of resedas (Reseda odorata, sweet mignonette) and red asters are to be brought into the house and placed “on the table”. Red, both the colour of passion and autumn (November in the Northern Hemisphere) and asters are typical cemetery flowers of Central Europe.

3. The table and the inside of the house

The table or house is also a symbol of the grave in many poems, for example Emily Dickinson’s “Because I could not stop for Death”:

We passed before a House that seemed A Swelling of the Ground-

The Roof was scarcely visible – The Cornice – in the Ground.

Reseda lutea

Reseda lutea4. Death

Death is ever-present in the song, but there is no morbidity. If anything, it is as if the sadness of death is made bearable by the connection with the dead made possible by the ceremony. It calls to mind Franz Schubert’s “Der Tod und das Mädchen” D531 to a text by Matthias Claudius. Death is the comforter. Here is an extraordinary performance by Christa Ludwig and Gerald Moore from 1961.

Musical treatment

The harmonic language is marked by quintessentially Straussian chromatic shifts. The modulations at the end of each strophe are quite dramatic, as if Strauss is trying to subvert the repeated strophic nature of the song by pushing it into a through-composed shape. Larger-scale tonal planning is obvious. On the words “deiner süßen Blicke” in the second strophe, a rather alarming shift to B Major, distantly related to the tonic of E Flat major, underlines the distance of the memory of the sweet glance of the beloved. Other Straussian trade-marks include the voice “creeping in” to the melodic material set out by the piano. At the entry of the voice at both the first and third strophe the voice seems to “complete” a thought started by the piano. In the great songs – “Morgen”, “Vier Letzte Lieder” – and great operatic scenes such as the closing scene of “Capriccio”, this technique creates tremendous unity of expression between the voice and its surroundings. The waves of graceful arpeggiated sweeps in the piano accompaniment throughout the song reinforce Gilm’s interpretation of All Souls’ Day, suggesting the yearning for the ideal springtime place where love is innocent and lovers are united in otherworldly bliss.

Useful links and recorded materials

Lotte Lehmann in a 1941 radio recital of the songs (1) Allerseelen, Op.10/8, (2) Zueignung, Op.10/1 and(3) Ständchen, Op.17/2 The uncredited pianist is possibly Paul Ulanowsky (1908-1968), her collaborator during this period.

Strauss first heard Lehmann (1886-1976) when she was the understudy for the heroine of his “Ariadne auf Naxos”. So impressed was he with her that she was entrusted with the world premiere. While never as comfortable in Liederas in the operatic repertory it is nonetheless valuable to hear a singer who performed these songs with the composer at the piano. Strauss’s wife Pauline de Ahna inspired many of his later songs and performed them often. Lehmann is said to have had a similar voice.

Jonas Kaufmann and Helmut Deutsch gives the lie to the fear that the golden age of Lieder-singing might be over. From a superb recital comes a superb rendition with much of the operatic vocal gesture for which Strauss’ songs are so famous, but allied with a true Lieder singer’s responsiveness to the text. Strauss’ operatic tenor roles might occasionally be unrewarding, but here is a most valuable contribution to the history of Lieder performance.

Briggitte Fassbaender performs here with an uncredited pianist – probably Irwin Gage – who underlines the cross-rhythms and couterpoint in a style which reminds one of the accompaniments of Johannes Brahms. Fassbaender’s tendency to overshoot climaxes is present here as well, but her way with the language, in particular touches of magic such as the conversational tone in the seconds strophe, marks her out as one of the great interpreters. View her in two Masterclass Excerpts on “Allerseelen”: Masterclass 1. Masterclass 2.

Jesye Norman and long time accompanist Geoffrey Parsons show why her enormous voice and powers of interpretation made her an ideal Strauss heroine. From the “Vier Letzte Lieder” to “Salome”, Strauss has formed a cornerstone of her repertoire from her early days of study in Vienna. While it is a big, powerful voice, one is struck by the intimate nature of this performance and the great control of pianissimi.

Kathleen Battle and mentor James Levine produce a delightfully intimate performance. A young artist in total control of her vocal equipment. Levine is delightfully fluid and “un-ponderous” in this live recording from 1983.

“Allerseelen” in a free translation by Walter Aue

“Allerseelen” sheet music

Upcoming performance of "Allerseelen"

My Blog has moved to www.albertcombrink.com

As a freelance pianist and accompanist I am always on the look-out for concert-fillers and interesting repertoire with which to fill out programmes. This posting is a companion-piece to my posting on operatic duets for Soprano and Mezzo. This list is work-in-progress and all input and suggestions will be greatly appreciated. I hope to update the list occasionally as my knowledge increases.

Purcell: Sound the trumpet /Two daughters of this aged stream /Let us wander

Purcell realised Britten: Sound the trumpet /Lost is my quiet for ever /What can we poor females do

Britten: Mother Comfort / Underneath the abject willow tree

Quilter: It was a lover and his lass / Summer Sunset (Perhaps more and Alto than a Mezzo)

Schumann – Liederalbum für die Jugend op.79

Mendelssohn: Wasserfahrt / Herbstlied /Volkslied op.65#3 /Abendlied (Heine) /Maiglöckchen und die Blümelein Op.63#6

Brahms – Duette op.20, op.61, op.66, op.75

Reger – op.111a

Berlioz: Le Trébuchet, op.13#3 /Pauvre, pauvre Colette /

Gounod: D’un coeur qui t’aime (Racine) /L’arithmétique /La Siesta /

Chausson: 2 songs op11

Saint-Saëns: Pastorale / El desdichado /

Delibes: Les trois oiseaux

Faure: Pleurs d’or op.72 /Tarentelle op.10#2

Massenet: Rêvons, c’est l’heure / Joie! /

Paladilhe: Au bord de l’eau

Rossini: La Pesca / La regata veneziana /Cat’s duet

Tchaikovsky: Duets op.46

Dvorak: (Moravian Duets) Op.31, Op.32, Op.43

Wennerberg, Gunnar: Marketenterskorna /Flickorna

Geijer, Erik: Dansen

Prof. Judith Kellock - Cornell University

My Blog has moved to www.albertcombrink.com

As part of her recital-tour of South Africa, Prof Judith Kellock, presented Masterclasses at S.A. College of Music at the University of Cape Town. It was a tremendous bonus that Peter Louis van Dijk and myself managed to get this to happen at UCT. At the invitation Prof. Virigina Davids – Head of the Voice Department at the SACM, Miss Kellock worked with students with a large range of skills, of both Under- and Post-Gradute level. Miss Kellock’s class drew substantial interest from faculty and students alike and was attended by all voice students and the full teaching faculty as well as UCT Alumni such as Belvedere Competition winner Pretty Yende. Miss Kellock’s informative class was characterised by her ability to go to the heart of what would provide the most beneficial information to each of the students in the limited time.

Miss Kellock focused on technical and expressive detail with each student. The meaning of the text and characterisation was emphasised in Lieder as well as Opera. Students were encouraged to think “outside the box” and experiment with material with which they were very well familiar. Technical themes that recurred throughout the class, were an excess of tension, muscular activity and “effortfulness” and Miss Kellock’s teaching assisted students to find a more direct approach to their performance. Very useful work included exercises to create fluid coloratura, creating meaning out of the text and French and German diction.

The students who performed were:

Sunnyboy Dladla (Tenor) – taught by Prof. Hartman – presented the taxing tenor aria “Vedro” from “La Scala di Seta” by Rossini. Sunnyboy performed the entire role of Dorvil in the Alex Fokkens/Lara Bye production earlier this year, where his comic flair and acting ability was matched by an outstanding vocal performance that won both audience and critical acclaim. Miss Kellock foccused on the coloratura runs in this aria. Her work with Sunnyboy on Rossini’s Bel Canto style contributed to his preparation for his upcoming role as Nemorino in the Cape Town Opera/UCT Production of Donizetti’s “L’Elisir d’amore”.

Friedl Mitas (Soprano) – taught by Prof. Davids – sang the “Jewel Song” from “Faust” by Gounod. Miss Kellock worked on making the interpretation more relevant to the dramatic context, and found innovative ways of making the aria fresh for the singer who had performed it many times. Friedl will be making her Debut with the Cape Town Philharmonic on Saturday 22 August in the CPO Youth Concerto Festival conducted by Theodor Kuchar.

Antoinette Blyth (Soprano) – taught by Dr. Liebl – performed “O! Quand je d’or” by Franz Liszt. As director of Cape Town’s Philharmonia Choir, Antoinette has extensive music experience as a choral conductor and voice teacher. Miss Kellock focused on aspects of breathing and tension held in the face. Most revealing was when she made Antoinette lie on her back and perform the song, as an illustration of breathing technique.

Phindiwe Nomyanda sang “Seit ich ihn Gesehen” from Schumann’s “Frauenlieben und -leben”. Work focused primarily on German diction and placing the song in context within the cycle.

Thembinkosi Mgetyengana (Tenor) – taught by Mr. Tikolo – sang Bellini’s “Ma rendi pur”. His clear voice and easily produced high notes impressed, and Miss Kellock worked on Bel Canto line and voice production. In particular, avoiding an over-active physical approach to the sound production was encouraged.

Accompanists for the Masterclass were UCT Vocal Coaches Kurt Haupt and myself Albert Combrink.

After the tremendous interest that our recital of American Song “Paper Wings” generated both in Cape Town and Port Elizabeth, students and faculty members were even more keen to benefit from Miss Kellock’s knowledge and experience, and we hope to have the privilege of having her back at the SACM in future.

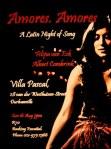

Amores, Amores: Filipa van Eck and Albert Combrink perform Latin American music by Alvarez and others

August 14, 2009

My Blog has moved to www.albertcombrink.com

Following our successful trip to Mozambique presenting Portuguese language music, Filipa and I have extended the Villa-Lobos portion of the programme to include a broad spectrum of Latin American gems. Amongst music from Cuba, Brazil and Argentina, the strains of Spain and Portugal are weaved in, reflecting not only their erstwhile colonial power and influence, but also the roots of the music from Latin America.

Our programme includes the famous and very popular “La Partida” (The Farewell) by Marcello Alvarez (1833?-1898). This beautiful song shows off the dramatic and vocal range of a singer and pianist, and makes an excellent recital-piece that has been recorded and performed by many great singers of the past and present. Alvarez is known for the composition of almost 100 songs and an unpublished opera “Margarita”. He also composed an orchestral work “Obertura Capricho” (Keith Johnson – All Music Guide)

The text by Spanish poet, playwright and journalist Eusebio Blasco Soler (1844 – 1903) tells of a person leaving their homeland with a heart full of sadness and even bitterness.

La Partida (The Farewell) – Eusebio Blasco Soler

Spanish Text: